Inspirations #1

‘Inspirations’ is our sometime feature where our writers delve into the genesis of their work and/or their creative process.

Follow the links to fall in love with them all over again, or visit our ever-growing Archive to discover new favourites.

Contents:

I wrote Raleigh 500 in the first Covid lockdown. Opening my ‘Story ideas’ file, I came across ‘Old man in Aldi queue, striped t-shirt’. Intrigued I clicked. I had absolutely no memory of it (this is why writers must, must, must keep a notebook!). Pretty much the whole outline was there. Almost everything I write (short stories, novels, plays) seems for some unknown reason to take place abroad, in some far-flung foreign destination, the Caribbean, Soviet Russia, France, India… If not, they open on the way to ‘abroad’ – in a departure lounge, parting the curtains of a sleeper car as the train pulls into an unknown city. Was I over-relying on exoticism to pull in my reader? Chekhov has a story called A Boring Story. I decided I needed to challenge myself to write one set in a banal UK setting. Where more so than my local Aldi?

I don’t think I’ve ever written a story so closely based on fact: I met an old man William Henshaw (not his real name) in an Aldi queue. He was about to set off home on his racer, overladen with shopping on one of Cambridge’s most perilous rush hour roads. I was terrified, and co-opted an African woman into helping me get the old man home in one piece. Neither have I ever written a more autobiographical story – the first person narrator has my name, lives in my road, and was born in Trinidad, to which William Henshaw announces straight off, ‘Capital Port of Spain.’

This and everything else is more or less as it happened – I’m having a job now remembering which elements I made up. I know my imagination placed the Waitrose Brioche Swirls (do they even exist?) into his bicycle basket. And I had him say ‘I used to drink Evian’ as I needed to show (not tell) how out of place this old gentleman seemed in the Aldi queue. But the best lines are all his (I couldn’t have come up with them):

‘No one to help out [at home]?’

‘I do have a brother in Brazil.’

I admit to having the African lady say that William had built her school in Mali, and I invented his shouting farewell to her in fluent (fictional) Bámbara.

A couple of years later, I actually visited the bungalow which we brought him home to in Brownlow Close. The fields it had looked onto were now a vast housing estate on Cambridge’s ever expanding city limits. It looked like someone else had moved into the bungalow. When I knocked next door to enquire, a new neighbour opened: the ‘old guy’ had gone into a home. So I never saw ‘William Henshaw’ again, though I looked out for him whenever I was in Aldi. The final scene where he rides on, safe and oblivious to traffic, across a busy junction is pure invention. Or wishful thinking.

Writing this has made me realise that I ultimately failed at my challenge. My story spirals out from the Aldi queue to Le Havre, Brazil, Trinidad, Mali…

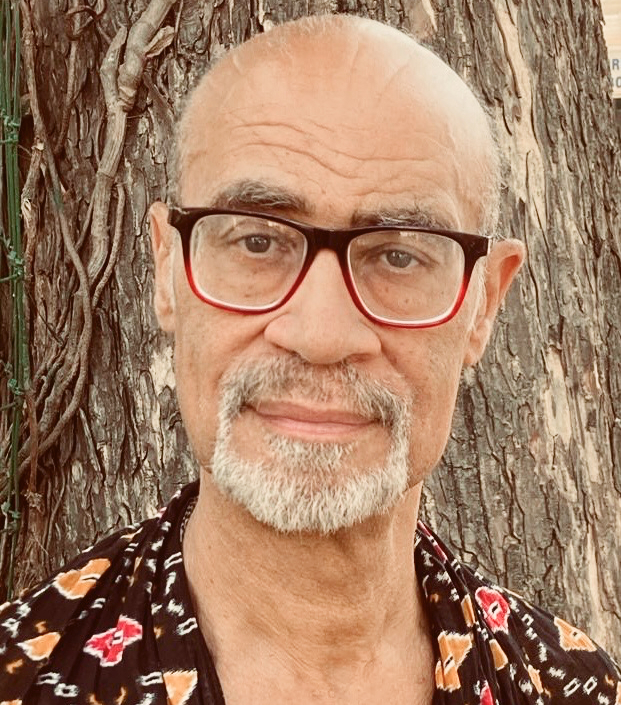

David and his wife Michèle run fantastic, affordable writing retreats in the South-West of France. For any writer working on a project of any size, these can’t come more highly recommended – our in-house editor has been twice! Find out more at the Le Verger website.

I have always been fascinated by the human body. As a young child I pored over medical textbooks, convinced that I would like to be a cardiovascular surgeon. In my teens and early adulthood, training as a professional dancer allowed me to really feel the anatomy I had spent so long trying to make sense of in my youth; I attempted to master that anatomy, perfect it.

Now, in my work as a psychologist I have applied a scientific lens to different aspects of the body, but with a view to understanding its inextricable link to the sense of a “self”. Here, I have traversed the realms of body image, physiological perceptions of internal body sensations (like feeling hunger and heartbeats), and conducted experiments that manipulate the sense of body ownership.

All of these different experiences have certainly informed my creative work: I hold close the hand of my six year old self; still trying to capture the visceral sense of my feelings, the anatomy of my heart.

Poetically, you could describe where I live as a storyteller’s tower: high above the rooftops of a medieval town, in a part of Bavaria where you can see the mountains pierce the Alpine sky on a clear day. (Most of the time it is like living in a continuous step class, trudging the five flights of stairs.) But when I’m writing, on those precious snatched days, I open my turret window and let down a braid: snatches of conversation from people on the streets – making for the cafes, browsing the little independent shops, taking a breather as the street’s gradient is grim – is a great way to hook a story, or hope one hauls itself up.

‘One Step at a Time’ didn’t heave itself up and in that way though. The creative spark for this one was a conversation with my partner on the sofa one evening after work as he shared a news story he had read in a German publication. It was about a retired teacher divulging her life lessons: that it is never too late to learn, and walking, preferably with a dog, is an ideal antidote to age. At the heart of the news story was a boy who loved Latin but, this being the take-no-prisoners German school system, he had lost his enthusiasm as he was in danger of failing the year. (Yep, you flunk enough tests here and you have to repeat the year!) The retired teacher decided to help him with his studies, despite knowing no Latin; the pupil started passing and that was pretty much it. At this story’s heart was a tale of unlikely friendship and persevering against the odds; it resonated, my being a teacher too, plus – hey, I had a rescue dog, I liked walking. So I thought, why not see what happens?

And what happened, sitting at my titchy little desk with just enough space for a laptop, a jar of chocs and a cup of tea, was the hauling in of a rather different story to the one my other half had cast me. There was no tension in this net, none at all; I realised that pretty quick and there was precious little back story. I wanted to write this with the British backdrop I knew from my own schooling in Kent and early teaching jobs in Cambridge, and this meant all the fear evaporated in the setting switch; there’s no need to fear a Latin test in the average British comp, if the subject is even on offer! So, I needed to think up a big spoonful of tension to help counterbalance the sweetness which threatened to cloy. I laced on Dulcie’s sensible shoes and walked about. What would send her out, day after day, beyond the need to walk her dog? What might be hiding behind those walks? Ideas came and the major theme shifted to grief, loss of many things, and stalking behind it all, the fear of losing even more.

What do I take away from this letting down and hauling in? Drawing from real life stories can be wonderful, but there’ll be plenty of legwork along the way. Tension, back story, and thematic revisions are just as likely to be needed as they are when plucking a story idea from the ether. Even if you live in a storyteller’s tower, there’ll be no waving of any wands to get the finished story on the page – although having a fairy godmother editor helps a lot!

It’s difficult to say much about Piranesi (Susanna Clarke, 2022) without giving the game away. What I can tell you is this: Piranesi lives in the House, and he spends his days documenting its birds, tides, and statues with a wonder-filled attentiveness. The novel’s second character is known only as the Other. He seeks a “great and secret Knowledge” in the House for his own gain.

For the Other, knowledge is power. For Piranesi, knowing is loving. I feel the same duality in me. Do I write because I want to gain some kind of power over my existence? Yes, sometimes. Do I write as a way of being attentive to life, as a form of love, without seeking control over the result? Well, I hope so. And I hope I can learn to do it more.

‘Accidents,’ for example, came from a sudden bereavement in my wife’s family. But I didn’t exactly write the poem because I wanted to write a poem. It was more that I found myself paying attention to my wife and me, to the loss, to other losses – and a poem began to coalesce.

Then, more than I worked on the poem, the poem worked on me. At that point I felt less like a vulture, circling around my life for materials to scavenge into a stanza, and more like an oyster: carrying a painful piece of grit that might result in a pearl one day. But of course, it might not. I think Piranesi would be okay with that.

Love this?

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter

- content updates, artworks, competition news (and frogs) - direct to your inbox

Read next: