Dead Man talking

Old Szymon Parker died while flower petals whirled themselves into soft gray pools of rain. I called him Creaky. He only left his apartment Sunday mornings to drink coffee and smoke on the patio at the diner on 2nd Avenue. In the winters, when he couldn’t smoke indoors, he’d take his coffee and lox with him to the river, where rusted industrial boats would sludge past him like forgotten dreams.

Creaky’s body always cracked in ways that made mine hurt. He’d turn to look at you with a pop. His hips moved like firecrackers, which I could hear often, as his bedroom window looked into mine and he always kept his open. We rarely spoke, yet he was often spoken about, mostly by the other neighbors — retired Eastern European women who had lived long, uninteresting lives and only spoke about others’.

Creaky had been a banker. No one remembered which bank it was. His parents had come to New York from Poland, but he changed his name to Parker because no one could pronounce the other one. He knew all the cigar rollers in the East Village, his favorite poet was Milosz, and he thought women wore ugly shoes. He was a Sagittarius.

I should feel bad for many things: that his nickname didn’t quite fit him; that I didn’t save his life. But, I only felt guilty for knowing so much about him, all of it against my will.

After the sirens came and went, Alina stomped on my door. She wore large leopard print boots and dyed her papery hair pink.

“Terrible about Szymon. But, the end is coming for all of us.”

“Yes,” I said.

“One day, Szymon. Next day, me.” She shrugged. “Or you.”

“Yes, yes.”

“They are telling us we can go through his apartment. Take what we like.”

“Who told you that?”

She pursed her lips and placed her finger over them, but never actually blew. I wished her a quiet evening.

Why would I want to go through Creaky’s things? I knew enough about the man, and anyway, I was tired of living other people’s lives. I was a journalist. I spent my days listening to people unzip themselves like luggage lost and found. Everyone had something to say about this city (it was going downhill), this world (it would end very soon), themselves (the only good thing in this city, this world). I didn’t know how much longer I could do it for. New York is a story that everyone is telling themselves, and I had gotten lost in it, a comma in the book of run-on sentences.

Besides, even though it was my job, I hated invading people’s privacies. When I was twelve, I found my father flipping through the drawings in my bedroom. Pictures of men, their hulking chests large and shaded, their dark eyes taunting me. I could feel myself pinned up against a wall whenever they looked at me. Yes, they were just adolescent doodles. But they were the first time I’d ever been seen. I remember my father’s cold gaze slicing through me, his blue eyes shivering me to stone.

“If you want a gym membership, just ask,” was all he said, then left the room. The shadow where he’d been standing continued to stare at me. We never spoke of it again.

At night, my neighbors swooped into Creaky’s. I imagined Alina’s cat-like eyes darting left and right, as if she was the only one sneaking in. I woke up several times to the sounds of gasps, groans, and laughter, and I imagined what Creaky could have owned to excite them like this. I always suspected he was gay. Did they find vintage pornos? A diary of old lovers? A vibrator? Perhaps Creaky draped himself in unwashed curtains and sashayed around his rent-controlled one-bed, painted lips pressed against his bathroom mirror. I fell asleep dreaming of this, of Creaky finally free before he croaked.

In the morning, more boots announced themselves against my doorframe. This time, I opened it to Angelika. Alina was hiding behind her, a full six inches shorter.

“Sonechko. Are you too good for us?” No one would tell me what “sonechko” meant, but Angelika called me one often. She held a brown, leather-bound journal in her hand. She smelled like my mother’s perfume.

“Oh. Sorry I didn’t join you last night. I wanted to respect Cr— Szymon’s privacy.”

Alina and Angelika looked at each other with expressions I was unequipped to comprehend. They looked back at me. “Well, Szymon didn’t respect yours.” She shoved the journal in my hands. “Read.”

They both stayed where they were, watching me. I flipped to a random page.

November 18

He likes to twist his wrist while he touches himself. He likes the taste of it on his thumb.

I didn’t understand. I looked at the women; they looked away. I tried a different page.

July 5

Sometimes he lets men enter him when he doesn’t really want them to. He can’t help saying yes when they want him so bad. Just because his body doesn’t trust them, doesn’t mean they can’t give him what he wants. To be wanted.

I flipped to the last entry.

April 27

This one kisses him terribly. He knows it. He wants to say it. Instead, all he says is

“Would you mind using a little mouthwash?” I looked up at Alina and Angelika. They both howled and clacked away.

I wanted to chase after them. Hurl the book at their backs and break them. Tear down the doors to their apartments, smash their dishes, steal their cooking, make them move out of the city. I saw them telling the secrets of my sex life to their new friends in Philly or Boca Raton, and thought, I should just put an end to their miserable lives anyway, since theirs aren’t even worth living, and I needed what little was left of mine.

Even then, I knew I was just the scared little bunny rabbit whose den had been dug out by a dying, harmless fox. All I could do was turn my back to the light and shiver.

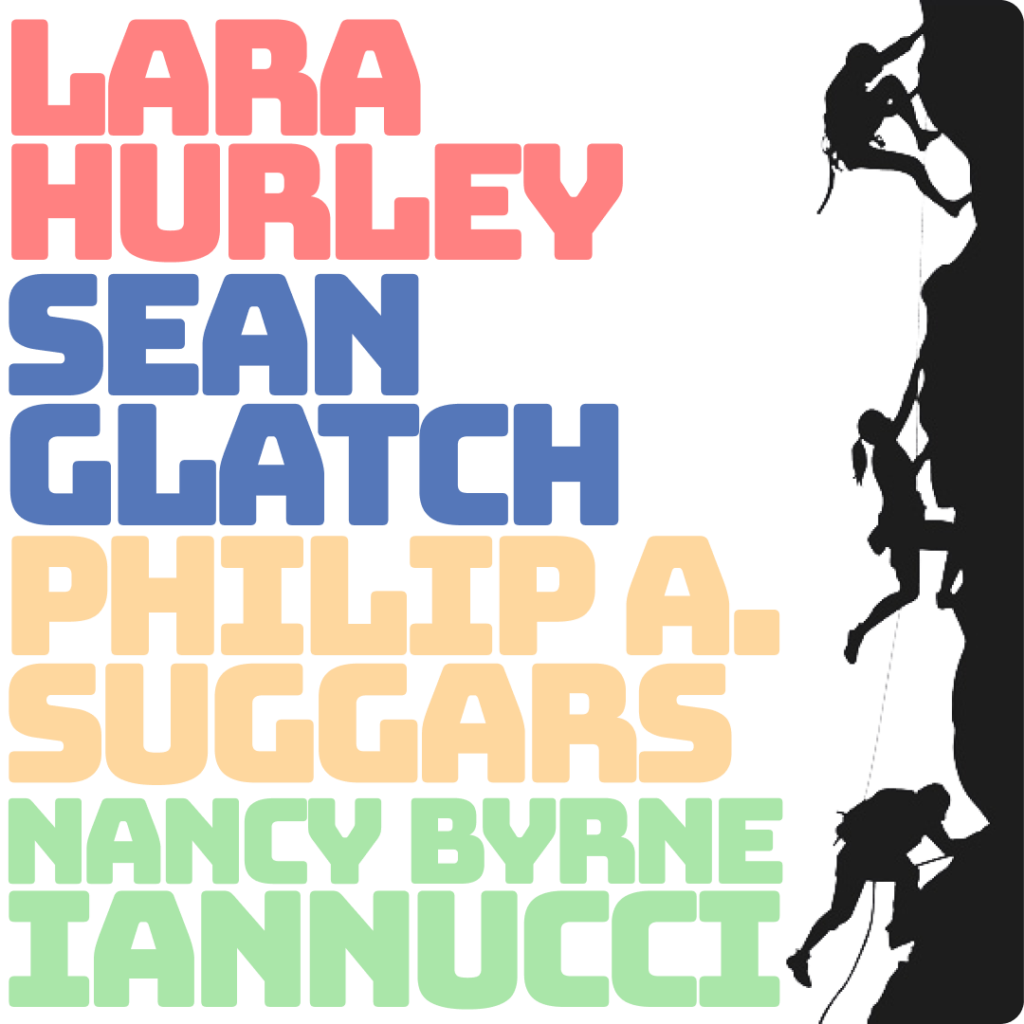

Sean Glatch

Sean Glatch is a queer poet, storyteller, and screenwriter living in New York City.

His work has appeared in Ninth Letter, Milk Press, 8Poems, The Poetry Annals, on local TV, and elsewhere.

Sean currently runs Writers.com, the oldest writing school on the internet. When he’s not writing, which is often, he thinks he should be writing.

Sean is also one of the judges of our writing competition, Britain vs The World: Flash Battle 2024.

More from this writer:

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter

- content updates, artworks, competition news (and frogs) - direct to your inbox

Read next: