raleigh 500

I saw him in the Aldi checkout queue adjacent to mine. He must have been in his late eighties, very large framed, in a childlike striped tee-shirt, a large man all hunched over. There was a sallowness about his eyes. Onto the conveyor he placed a twelve-pack of green 500 ml bottles of mineral water. Next, some iced tarts, and two four-packs of cream of tomato soup, a tin of potatoes, a jar of strong English mustard. I noticed blood bruises on one arm, and a circular pink plaster they stick on you when they take blood. When it was his turn, he said something to the brisk cashier with Snežana on her name badge, which made her soften into a smile. His shaky hands stuffed the purchases into a battered canvas rucksack with leather straps and buckles. As he was paying, he dropped a five pence piece and it rolled over to my queue. I went to pick it up but he was on it.

‘You alright, love?’ said the cashier concerned once he’d paid and was taking up his heavy rucksack. His purple fingers gripped the plastic skin of the mineral water pack.

‘I can manage,’ he smiled. Then he walked over and put his groceries on the packing counter. I stopped beside him to arrange my few purchases. He couldn’t stuff everything into that rucksack. I picked up a small cardboard box and offered it to him.

‘That’s very kind of you.’ He was very well spoken.

‘That’s a lot of mineral water,’ I said.

‘I much prefer still to fizzy.’

‘Heavy to carry,’ I continued. ‘Do you not drink water from the tap, less to carry?’

‘I used to drink Evian, only now it’s beyond my means.’

Fine tastes. ‘I’ll help you get it out front,’ I said, hoisting my own ruck sack onto my back and holding out my hand for the mineral water.

‘No, I can make it. I don’t live far. Blackheath Close, number 18, second on the left towards the motorway.’

The motorway started quite a way outside town. ‘How will you walk out there?’

‘Oh, I’m not walking.’ Of course, he’d have someone picking him up. ‘I’m on my bike.’

‘…You’re cycling?’

‘I’ve got a basket and panniers.’

I pictured him wheeling home a top-heavy bicycle.

Outside the store, I followed him over to an old green Raleigh 500 with a drooping wicker basket already full of shopping. I noticed Waitrose Brioche Swirls with chocolate bits. The two rear panniers too were laden. I attached the box and the mineral water pack to the back rack with its frayed elastic, while he got out his keys and started to unlock.

‘Very kind of you,’ he said standing up straight now to get a good look at me. His eyes were sharp blue and inquisitive, and I saw that the sallowness I’d noticed round eyes was quite severe bruising.

‘Where’ve you come from?’ he asked.

‘I live in Roseford Road,’ I said. ‘It’s on the way.’

‘No, I mean which country?’

‘Oh, sorry. The West Indies. Trinidad and Tobago?’

‘Capital Port of Spain,’ he nodded.

It’s pretty much only cricket fans, serious bird watchers and carnival revelers who can name Port of Spain. Most people are unsure of the country so you have to say near Jamaica, and they say Ah Jamaica! and then you tell them it’s actually a thousand miles south of Jamaica, and they look a bit confused, so sometimes, especially abroad, it’s easier to just say you’re from Jamaica and they immediately go Bob Marley! and want to bump knuckles. It makes for instant connection but you feel a bit of a fraud. And here’s this old guy getting Port of Spain spot on.

‘I was born in France you, know,’ he said.

‘Oh? Whereabouts?’

‘Le Havre,’ he said, wistful. ‘I’m English now though.’

I unlocked my bike which was near his, and we started to wheel them through the car park towards the main road.

‘Do you have someone at home?’ I asked.

‘No, I’m on my own.’

‘No one to help out?’

‘I do have a brother in Brazil,’ he said.

His front wheel gave a regular squeak under the weight of groceries.

‘Will you manage to push it home?’ I asked as we reached the busy road.

‘No, no,’ he said. ‘I’m riding it.’

The traffic on Histon Road is frightening at the best of times. At 5:30 rush hour it’s murder. Buses roar by, and lorries trundling out to the A14 and M11 growl, their hydraulic brakes hissing out a warning. I suggested the overloaded bike was not safe to ride, he was better off pushing it.

‘I’m not that good on my pins,’ he said. ‘Cycling’s easier, I’ll be fine, I’ve done it before.’

He went to raise his leg over the saddle and might have managed it but for the box I’d attached on the back. Because his trousers were falling down, the low crotch couldn’t clear the high saddle. I regretted not having my car; I could have driven him to his door with his bicycle in the back. I steadied the bike now while he unbuckled his belt and hitched up his trousers with their gaping fly, where, at the seam, I noticed a large stain.

‘You really can’t cycle in this traffic…’ I said.

‘I’ve done it before,’ he repeated, tugging his belt tight. ‘Getting on’s never easy but once in the saddle I’m away!’

My mind was a lurid movie reel – the old man caught in the wind from a monster juggernaut, him wobbling, losing his balance, crashing down onto the tarmac and disappearing under the wheels of an oncoming Citi-bus, mineral water bottles slithering across the road, spoked wheels turning uselessly at the sky, and the brief but eternal silence before the distant wail of emergency services. He wasn’t even wearing a helmet.

I looked around the carpark, and spotted a trolley. We’d load up his shopping and push it home. I wasn’t that sure where Blackheath Close was. ‘Out towards the motorway,’ he repeated. He might have the direction entirely wrong, though he seemed pretty clear-headed.

‘Hold onto your bike,’ I instructed him as I lent my bike against a wall. ‘I won’t be a moment.’

‘Where’re you going?’ he asked.

Before I got to the trolley, I already knew my plan wouldn’t work; the store would have security cameras operating, or the wheels would lock beyond the car park precincts. There was a loud crash behind me. I turned to see the Raleigh a twisted heap on the ground, tins of tomato soup rolling away, the old man still standing adjusting his belt buckle. I rushed back.

‘Toppled over,’ he said, only slightly dismayed. With the full panniers, the box I’d attached to the rack had only made the bike more unstable. I struggled to restore the unevenly weighted contraption to the perpendicular and then, while he held the handlebars, retrieved the dented soup tins.

‘You can’t ride on this road at rush hour,’ I said. ‘It’s lethal’

‘I’ll be fine,’ he said brightly. ‘Done it before.’

He’d think me patronizing, preventing him from going about his life. Just because he was old. My mind kept replaying the film of him coming off his bike. And what about the driver whose bus he ended up under? The passengers on their way home? Their lives would be ruined too.

A large black woman was unlocking a car near us.

‘Hold the bike steady,’ I told him. ‘I’ll see if we can get someone to help us.’ I approached her as she climbed into a high, silver four-wheel drive and closed the heavy door. The rear windows were tinted black so I couldn’t see in.

‘Excuse me,’ I said at the driver’s window. She shook her head. Surely she didn’t think I was asking for spare change. ‘Sorry,’ I persisted. I could see she was a little intrigued by a middle-aged mixed-race guy importuning her in the car park. I motioned over to the old man. He was holding the handlebars at a precarious angle with the heavy basket twisting the front wheel around. It looked like the bike could go down again at any moment. I saw the woman’s eyes widen. She lowered her window a crack. ‘I don’t suppose you could help me out?’ She opened the window wider. ‘It’s too dangerous for him to cycle, says he only lives around the corner.’

‘I have my daughter in the back.’ She had a pronounced African accent. I glanced into the car but could see nothing through the dark windows. There was a crucifix hanging on rosary beads from her rear-view mirror.

‘Okay, I’ll ask someone else.’

‘No, wait,’ said the woman, opening the door.

She got down from the high car, well-dressed in a tailored suit, and we walked over to the man.

‘Are you okay?’ she asked him, business like, and bent to pick up the couple of groceries that had fallen out of the basket.

‘Very kind of you,’ said the old man.

‘Pleasure. Now, do you know where you live?’ she asked. It was the voice of a professional.

‘18 Blackheath Close, second on the left towards the motorway, far end of the close on the right.’

‘What’s your name?’ she asked.

‘William.’

‘Brilliant, William, now we’re popping you and your groceries in my car, alright?’

‘What about my bike?’ he said.

I offered to cycle it to his house. I hoped he had the address right or they’d drive off and I’d never find them. We got to her car, heaved him up into the front seat.

‘This is all very kind of you but there’s really no need,’ he said, gazing around him.

‘Pleasure,’ she said. ‘We’ll soon have you home, William.’

She opened the rear door to stow all his shopping, and on the rear seat I saw a wide-eyed seven-year-old, her head a patchwork of pink woolly hair ties.

‘I’ll follow behind you,’ the woman told me.

‘I think William knows the way,’ I said.

I waved at them as they headed off through the car park to join the main road. As I pushed his bike out to the road I expected to see them joining the traffic streaming by. I waited, scanning the traffic rumbling past. No silver four-wheel drive with a mean expression to its headlamps. What had become of them, had he directed her another way? Perhaps I’d missed them and they’d somehow got ahead of me – one make of computer-designed car looks much the same as any other these days. As I tried to push off, my foot went straight down, the pedal span free in the air and painfully into my shin: the chain was off, probably from when the bike fell. Cursing under my breath, I bent over and struggled to get the thing back on, my fingers oily black. But I was anxious I’d miss them, and had to keep looking up. I decided to push the disabled bike as fast as my throbbing shin would let me.

I limped for some time with no sight of them. Perhaps they were already waiting outside the old fellow’s house, wondering where I’d got to with his bike. I jumped on the saddle and pushed myself along with my feet. I looked an idiot, but it was faster than limping. Traffic thundered past. I flinched at an ear-splitting series of brassy blasts: La Cucuracha! A carful of jeering youths shot past making obscene gestures out the windows.

I’d passed the first turn off, so Blackheath should have been next. But as I stopped at the next turning the sign said Brownlow Close. Not Blackheath. Beyond, the houses petered out and there was a clear road out to the motorway roundabout, big signs for the A14 and M11, London and The North. He was entirely delusional, making it all up. He’d escaped his care home. Who knew where he’d got the money to buy Waitrose Brioche Swirls. ‘I used to drink Evian.’ Looking back, his birth in Le Havre did throw me, though I’d bought it at the time. More likely he’d served there in the war. Or caught the ferry on holiday. The brother in Brazil should have alerted me.

And here I was with his bike and its empty basket and panniers at Brownlow Close looking for a fictitious Blackheath Close, and I’d lumbered the poor African lady with him. She’d no doubt work out a way to get him back to the home. A car honked at the end of the close. Its headlamps flashed twice. A hand was waving to me out the window.

It takes a millisecond for the mind to commit to an imagined scenario, and as long to dismiss it, and invest in another – or return to the original scenario it has just discounted. Relieved, and not a little sheepish, I rode in my fashion into the close towards the car. As I approached, attached to the low brick wall I saw two signs succeeding each other: Brownlow then Blackheath Close.

The woman had backed onto the drive in front of a row of bungalows. She got out as I came up.

‘Sorry you had to wait… Chain came off,’ I panted, holding up my oily hands as proof.

She flashed a smile and gave a deep chuckle, large teeth. ‘William’s been telling me about his time in Bamako,’ she said, starting to unload his shopping. ‘Turns out he built my old school there!’

The old man was pushing the heavy passenger door open and maneuvering his way down. I leaned his bicycle against the low brick wall.

‘I have to get my daughter to Brownies,’ she said. ‘Brown Owl freaks out if they’re late.’

I thanked her for her help.

‘What’s your name?’ I asked.

‘Patience.’

That deep chuckle again, her large shoulders shook. She was well named. From the driver’s seat, she called to William to take care. He raised his hand in a wave and shouted something like ‘Abangó mama-saa!’ There was a shriek of laughter as the car drove off down the close, her raised hand waving out the window.

The front door of one of the bungalows opened and a young woman came out.

‘Hiya, Bill,’ she called. She didn’t seem surprised to see strangers bringing him home.

‘So he lives with you?’ I felt relieved.

‘No, I’m the neighbour, that’s him next door.’

I looked at number 18, the overgrown rockery, the ragged uncut grass either side of its front path. William had picked up his shopping.

‘Oh, you’ve brought my bike,’ he said, surprised at seeing it. ‘Very kind of you.’ He fumbled in his pockets for his front door keys.

‘Sorry about the chain,’ I said but I don’t think he heard. ‘At least it’ll keep him off the roads,’ I said to the neighbour.

‘Chance’d be a fine thing,’ she laughed. ‘Headstrong old bugger.’ She raised her voice to him. ‘Don’t worry, Jack’ll fix your chain, Bill. You’ll soon be back on your bike.’

‘That wise?’ I said.

‘Try stopping him,’ she laughed.

William had by now opened his front door. Curious, I followed him into the bungalow with the shopping, while the neighbour put the bike at the side for Jack to repair.

Inside I expected a stale smell of old man and sour vegetables, but it was surprisingly fresh, shoes lined up neatly in the hall, and a view through to the living room of two upright armchairs, an electric fire and book-lined walls. In the little kitchen, dirty pots stood on a hob deeply encrusted with cooking sauces. A slice of blackened toast lay on the counter.

‘Well it was nice meeting you,’ I said once I’d helped him unpack the groceries. ‘My name’s David.’

‘William Henshaw,’ he said, offering me his large hand. ‘Cup of tea!’

‘Love to, but I’m packing,’ I said. ‘I’m off to France tomorrow.’

‘What part?’

‘The south-west, near Bordeaux. You said you’d lived in Le Havre, was it?’

‘Born there,’ he corrected as he saw me to the door.

‘And do you speak French?’

‘Mais bien sûr.’ His accent was convincing.

‘I’ll pop by when I get back, if I may,’ I said.

‘Et beh, ce sera avec grand plaisir,’ he responded. ‘Merci infiniment!’

I walked down the close. As I looked back, William Henshaw was chatting with the neighbour on that warm summer evening.

I never did visit him when I got back from France. The truth is he entirely slipped my mind. Then one day, at the Aldi check out, the person in front of me dropped a coin and I was reminded of the old man. I promised myself I’d knock on his door. But again, months went by, then a year, and I never did. Nor did I ever see him again struggling along busy Histon Road with shopping on his bike or on foot. I hoped the neighbour had been sensible enough not to repair the bike chain, and that he was now making use of Dial-a-ride for elders. Sometimes, when I read the local paper, in the Births and Deaths section, I found myself scanning the names for that of William Henshaw.

Then about eighteen months later, on a grey November afternoon, my car was just pulling up to a red light at the intersection right over by Milton Road, when a cyclist rode past me. They take up position in front of the cars so they can be first away when the lights change. Only, this cyclist didn’t stop at the red light but continued pedalling resolutely on into the middle of the intersection and the stream of accelerating traffic, hunched over his bike, a bulky gabardine coat, a battered rucksack, the front basket almost hanging off. William Henshaw.

‘…Stop!’ I shouted uselessly at the windscreen, then jabbed frantically at my horn. On he went into the path of oncoming vehicles. There was a terrible protracted screech of brakes and I shut my eyes waiting for the sickening thud, with a horror film unspooling in my head. But no thud came. I shouldered open my door and stood with my heart in my mouth. Out in the wide junction I saw William, head down, pedalling on. The car that had screeched to a halt astride the intersection was bumped surprisingly gently and as if in slow motion by a van from behind, and there was the tinkle of glass. The van driver wound down his window and actually shook his fist in cartoon rage at the driver in front of him. Other vehicles swerved in a slowed down balletic dance. One had its hazard lights on and a car alarm started up a persistent beeping.

His rusty bike weighed down with shopping, the old man in the gabardine coat, who was born in Le Havre, and lived alone but had a brother in Brazil, and had built a school in Bamako, reached the far side of the intersection oblivious, and pedalled on.

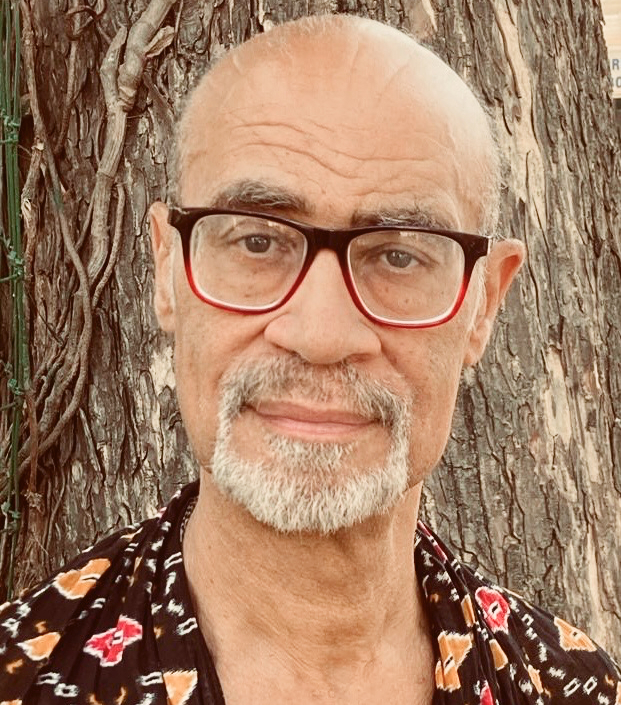

David Lambert

David Lambert is a playwright, poet, novelist and the author of numerous short stories.

He has a Masters in Creative Writing from UEA, and taught at Anglia Ruskin University for 13 years. He is a winner of the Norwich Prize (2002) and was selected for the Royal Court Writers Studio (2012).

His novel set in the Caribbean, The House on Bacolet, will soon be published by Peepal Tree Press.

Born in Trinidad, he lives in Cambridge, and runs writing retreats in South-West France.